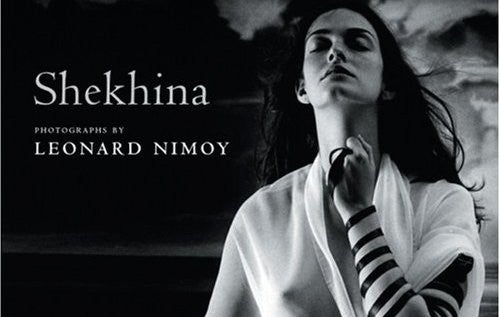

When you think of Leonard Nimoy, who died last week, you’re probably more likely to think of the pointy-eared Spock than of scantily dressed women.

But in 2002, the actor best known for his role on “Star Trek,” generated a small storm with his black-and-white photographs of women clad in nothing but prayer shawls and tefillin, the leather phylacteries traditionally worn by men during weekday morning prayers.

In an October 2002 interview with JTA, Nimoy insisted that his photography book “Shekhina” was not “in the Mapplethorpe territory” — referencing the controversial artist known for his graphic photographs of gay sex.

The storm over “Shekhina” — a kabbalistic term for the feminine aspect of the divine spirit — erupted after Nimoy embarked on a nine-month, 26-city promotional tour of Jewish book fairs, JCCs and synagogues.

He defends the photos as part of a longtime journey into his Jewish roots, and a trek into exploring the feminine aspect of God.

In the book, many of Nimoy’s nudes are accompanied by quotes from such Jewish thinkers as Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook and biblical tales of Kings David and Solomon.

“I’m not introducing sexuality into Judaism; it’s been there for centuries,” he said. “The Sabbath Bride is the shekhina. It’s always been considered a mitzvah, a commandment, that husbands and wives should have sex Friday night to usher in the Sabbath.”

JTA interviewed Nimoy soon after he backed out of an appearance at the Jewish Federation of Greater Seattle’s annual fundraising dinner, following a dispute over his desire to show slides and discuss his monograph.

“I expected more of an open-minded community,” Nimoy said of the Seattle federation. “I think they were more interested in entertainment than illumination.”

Barry Goren, executive director of the Seattle federation, said the group was not trying to act as some kind of “Ayatollah Khomeini,” but felt it wasn’t a good idea to have Nimoy show potentially controversial slides at a fund- raising dinner.

Leonard Nimoy (L) and wife Susan Bay arrive at the premiere of Paramount Pictures’ “Star Trek Into Darkness” on May 14, 2013 in Hollywood. (Kevin Winter/Getty Images for Paramount Pictures)

Instead of speaking at the federation dinner, Nimoy promoted his book at a local Reform synagogue whose rabbi told JTA that while it would have been inappropriate to show images from the book at the federation dinner, it was important to allow Nimoy’s photographs to be seen elsewhere in the Jewish community.

“We have to make sure our Jewish community doesn’t become intellectually empty and culturally frozen,” he said.

In the same article, Richard Siegel, executive director of the National Foundation of Jewish Culture, described Nimoy as a “serious artist” who is “undertaking a serious exploration of Jewish spirituality.”

The “Shekhina” project wasn’t Nimoy’s last Jewish provocation. In 2011, he wrote an open letter published on the Americans for Peace Now website calling for a two-state solution with a divided Jerusalem, despite the mainstream Jewish community’s opposition to dividing the city.

Nimoy made a “Star Trek” episode reference to help prove his point:

You might recall the episode in the original Star Trek series called, “Let That Be Your Last Battlefield.” Two men, half black, half white, are the last survivors of their peoples who have been at war with each other for thousands of years, yet the Enterprise crew could find no differences separating these two raging men.

But the antagonists were keenly aware of their differences–one man was white on the right side, the other was black on the right side. And they were prepared to battle to the death to defend the memory of their people who died from the atrocities committed by the other.

The story was a myth, of course, and by invoking it I don’t mean to belittle the very real issues that divide Israelis and Palestinians. What I do mean to suggest is that the time for recriminations is over. Assigning blame over all other priorities is self-defeating. Myth can be a snare. The two sides need our help to evade the snare and search for a way to compromise.